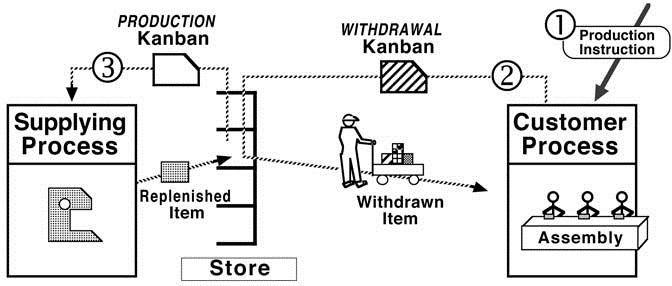

The traditional approach for regulating production, which is still in wide use, is that each process in a value stream gets a schedule. These schedules are based on predictions of what the downstream processes will need in the future. Since humans, even with the help of computer software, cannot accurately predict the future, this approach is called a “push system.” That is, each process produces what we believe the next process will need and pushes that material on toward the next process. The alternative approach for regulating production—Toyota’s “pull,” or kanban, system—is by now also well known, and its basic mechanics are summarized in Figure 5-12.

- The customer process, here assembly, receives some form of production Perhaps this is a leveled production instruction as described on the previous pages under heijunka.

- The material handler serving this assembly process regularly goes to the upstream store and withdraws the parts that the assembly process needs in order to fulfill the production

- The supplying process then produces to replenish what was withdrawn from its

The difference with the pull approach is that production at the supplying process is regulated by the customer process’s withdrawals from the supplying process’s store, rather than by a schedule. In this manner the supplying process only produces what the customer process has actually used, and the two processes become linked in a customer/ supplier relationship.

Figure 5-12. Basic kanban, or pull-system, mechanics

These mechanics of the kanban system are what we benchmarked at Toyota, and those mechanics are what we have been trying to implement in our factories for many years. However, as with leveling, our success with pull systems has not been so good. In many cases what begins as an effort to introduce a pull system devolves into just betterorganized inventory, and the supplying process continues to produce to some kind of a schedule.

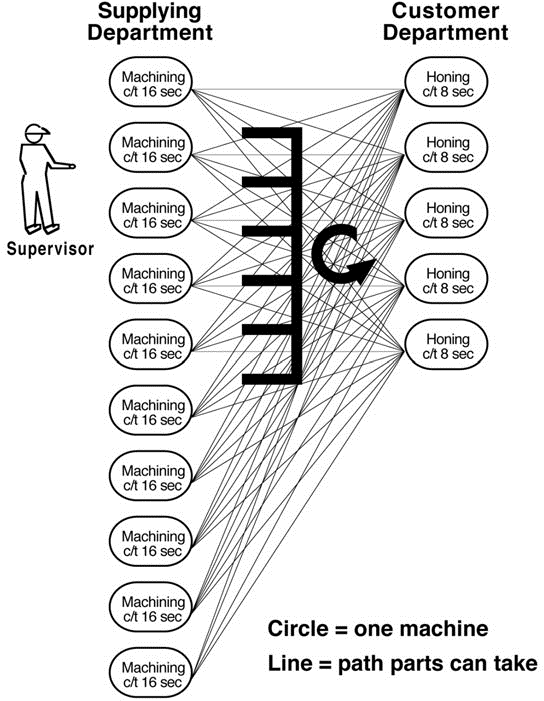

Let us use the depiction in Figure 5-13 of a material flow between two production departments to take a deeper look at Toyota’s kanban system. Each circle in the diagram represents one machine, and there are multiples of the same machine in each department. Each line in the diagram represents a path that parts may take, and any part number can be run on any machine.

As is suggested by all the lines, currently the supplying department runs parts on whatever machine is available at the time. Also shown is the supervisor of the supplying department. Now assume that we would like to insert a supermarket (kanban system) between these two departments, as shown.

Perhaps we are doing this because the departments are located far apart, or maybe the machines in the supplying department have vastly different change-over times than those in the customer department.

Figure 5-13. Material flow between two production departments

To set up this pull system, we will need some information, which includes, among other things, part numbers, quantity, and the following two locations, or “addresses”:

- Where, in the supermarket, the parts associated with a kanban card will be kept

- On what machine the parts associated with a kanban card should be produced

The act of specifying the second address—of defining what parts should be run on what machine—helps us to see what kanban is really about at Toyota. How do you think the supervisor will respond if we ask him to define what parts run on what machine?

The supervisor is likely to object to someone taking away his flexibility to run the parts on whatever machine is available. Perhaps he will say something like, “If we are going to define what parts will run on what machine, and thereby reduce my ability to run items on any machine, then we better start improving the reliability of these machines.” And so kanban has already started working for us. It has shown us an obstacle, and now we need to roll up our sleeves and look into that problem.

I have heard many managers and engineers say, “We tried the kanban system, but it doesn’t work here.” To this, a Toyota person might well say, “Ah, kanban is actually already working. It has revealed an obstacle to your progress, which you now need to work on and then try again.” We gave up at the place where Toyota rolls up its sleeves and gets going.

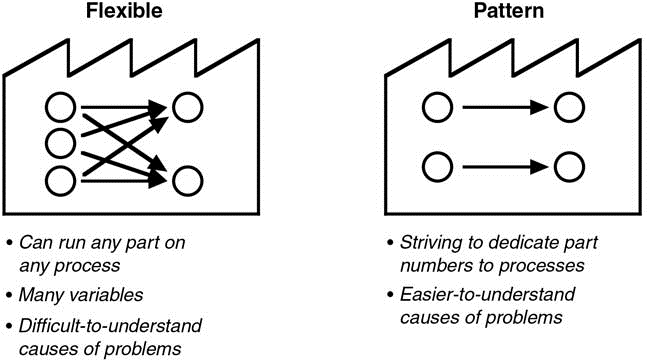

Figure 5-14. Two different approaches

It is the same point again. Whether all those crossing lines—the flexibility to run parts on any available machine—look good or bad to you depends on your purpose (Figure 5-14):

- If your purpose is “make production,” then the flexible system looks good because despite the existence of problems you can work around them and still make the

- If your purpose is “survive by continuously improving,” then the flexible system looks In fact, operating this way is not permitted at Toyota.5Working around problems by making the same part here and there increases the number of variables and makes understanding the cause of problems considerably more difficult. Flexible systems that autonomously bypass problems are by their nature nonimproving. You may make production today, but will you still beat the competition tomorrow?

The Intention Behind Kanban

The overt, visible purpose of kanban is to provide a way of regulating production between processes that results in producing only what is needed when it is needed. The invisible purpose of kanban is to support process improvement; to provide a target condition by defining a

desired systematic relationship between processes, which exposes needs for improvement. In a push system, processes are disconnected from one another and routings are too flexible. There is no target condition to strive for.

. . . according to Ohno, the kanban controlled inventories . . . served as a mechanism to make any problems in the production system highly conspicuous . . .

—Michael Cusumano, The Japanese Automobile Industry

The difference between the visible and invisible purposes of kanban is very much the difference between the implementation and problem solving orientations I described in Chapter 1. We have been trying to implement the visible purpose of kanban without the invisible problem-solving effort, but one does not work without the other. No matter how carefully you calculate and plan the details of a pull system, when you start up that system it will not work as intended. This is completely normal, and we are setting ourselves an impossible target if we think we can achieve otherwise. What we are actually doing with all our careful preparation for a pull system—as with so many Toyota techniques—is defining a target condition to strive for.

My colleague Joachim Klesius and I once visited a large, 6,000person factory that had decided to get into lean manufacturing. When we asked the plant’s management what their first step would be, the answer was, “We will be introducing the pull system across the entire factory.” This not only reveals our flawed thinking about pull systems, it also simply cannot work:

- Anytime you start up a pull system, it will crash and burn within a short There will be glowing and charred pieces, so to speak. But it is precisely these charred and glowing pieces that tell you what you need to work on, step by step, in order to make the pull system function as intended. Your second attempt to make that pull system work may then last a bit longer than the first, but it too will soon fail. And again you will learn what you need to work on. This cycle will actually repeat, albeit with longer intervals between the problems, until someday you have a 1x1 flow and no

longer need the pull system. Keep in mind, by the way, that the kanban system does not cause problems, it only reveals them.

- Pull systems are rarely the first step in adopting lean manufacturing. Many production processes are currently unstable, and the amount of inventory you would need in order to have a functioning pull system between unstable processes would be unacceptably That much inventory would be detrimental anyway, since you would be covering up instability rather than first setting other process target conditions that help you understand and eliminate that instability.

If kanban is a tool for process improvement, then it makes sense to introduce pull systems on a small scale first and expand step by step as we learn more about and improve the relevant processes. If we try to introduce kanban quickly across an entire factory, an unmanageable number of problems will surface. Toyota’s organization could not handle that either.

All this means that just introducing a kanban system by itself will improve very little; the system only mirrors and sheds light on the current situation. It does not, for example, by itself reduce inventory. It just organizes and utilizes inventory.

This in turn means it is impossible to implement a pull system. We should think of and use the pull system as a tool to establish target conditions in our effort to keep improving toward the ideal state condition. Each state we achieve is simply the prelude to another.

This last point was made clear by remarks from two Toyota people. The first was: “The purpose of kanban is to eliminate the kanban.” While I was still pondering that one, I heard another Toyota person say: “We don’t know how you make progress without kanban.”

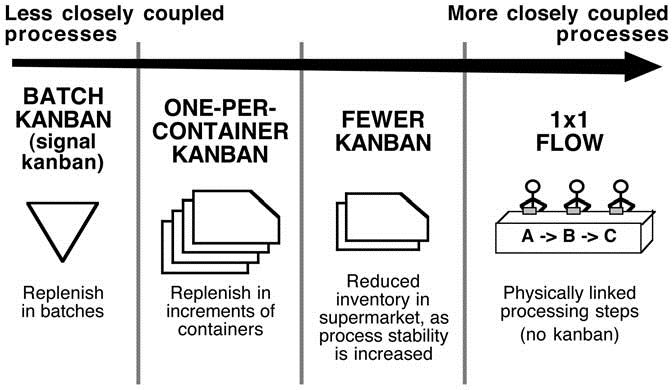

Ah-ha! Kanban is a tool to help us shrink the supermarket (inventory) over time and move progressively closer to 1x1 flow. That is why when a kanban loop at Toyota has been running trouble-free for some time, a manager might remove a kanban card from the loop. In this manner inventory is reduced, in a controlled fashion, and problems can begin surfacing again. Kanban is used to define successive target conditions, on the way to a 1x1 flow (Figure 5-15).

Figure 5-15. Kanban allows us to define challenging target conditions on the way to a 1x1 flow