Why Does Your Company Exist?

What Is Your Company’s Philosophy?

Ask this simple question at work and watch the eyes glaze over. It is a bit like asking why humans exist on this earth. Leave that to the philosophers. Let’s get down to the work we have to do today. Companies regularly have retreats where plans are made for the next year, and some forward-thinking companies even develop five-year plans. But then we hear about the mysterious 500-year plans of Japanese companies. It is not necessary to know what your company will be doing in 500 years. The question is whether your vision includes being around that long.

Toyota’s vision certainly does include being around for the long term. Starting as a family company, it has evolved into a living organism that wants first and foremost to survive in order to continue contributing. Contributing to whom? Contributing to society, the community, and all of its associates and partners.

If we ask why most private companies exist, the answer comes down to a single word: profit. Any economist can tell you that in a market-driven economy the only thing a company needs to worry about is making money—as much as possible, within legal constraints, of course. That is the goal. In fact, any other goal will lead to a distortion of the free market.

Let’s consider a simple thought experiment. If a sound financial analysis demonstrated that your company could be more financially valuable if it were broken up and the assets sold off rather than continuing as a company, would your leaders do it? Would they be fulfilling the purpose of the company by dissolving it and selling off the pieces?

From a pure market-economics perspective they should dissolve the company and sell it off. Of course, one could argue that it depends on the terms being considered. Perhaps with a change in strategy the company could be more profitable in a 10-year period compared to dissolving it. Or perhaps one has to look out 15 years. But the time period is not the issue. The issue is: Why does the company exist? If it is purely a financial endeavor, it could achieve its purpose by being profitably dissolved and sold off based on risk-reward calculations over some time horizon. If the company exists for other reasons, then selling it off, even at a tidy profit, may be admitting failure.

If Toyota were broken into pieces and sold off at a handsome profit, it would be an utter failure based on its purpose. It could not continue to benefit society, let alone its internal associates or external partners, if it were dissolved as a company. It would only benefit a few individual owners in the short term. This is an important fact as a foundation for building a lean learning enterprise because it leads to the fundamental question: What is it worth investing to achieve the purpose of the company?

For every business transaction this question will come to the fore. For every investment in improving the company, its people, and its partners, this question will loom large. In fact, if you can’t answer this question, it may not be worth learning to be lean. You might want to pull a few of the lean tools out of the lean bag of tricks and map your process, eliminate some waste, and grab the cost savings. But you won’t become a lean learning enterprise by taking that path. And most of the good advice and tips in this book will not apply to your company. Read a book on financial analysis instead.

So at some point you need to face the tough question: Why do we exist as a company? It need not be an abstract, unanswerable, philosophical debate. In this chapter we discuss a way of thinking about your company’s purpose and some tips on what it takes to develop the foundation for building a lean learning enterprise.

A Sense of Purpose Inside and Out

What does it mean for an organization to have a sense of purpose? If it’s simply to make money, put a big dollar sign on a poster for the employees and managers to see and forget the elaborate mission statement. If it’s more than that, you should consider what you’re trying to accomplish both internally and externally. What are you trying to build for your internal stakeholders? What are you trying to help them contribute, and what will they get in return? What impact are you trying to have on the outside world? Furthermore, your mission should have two parts—one part about people and the other about the business.

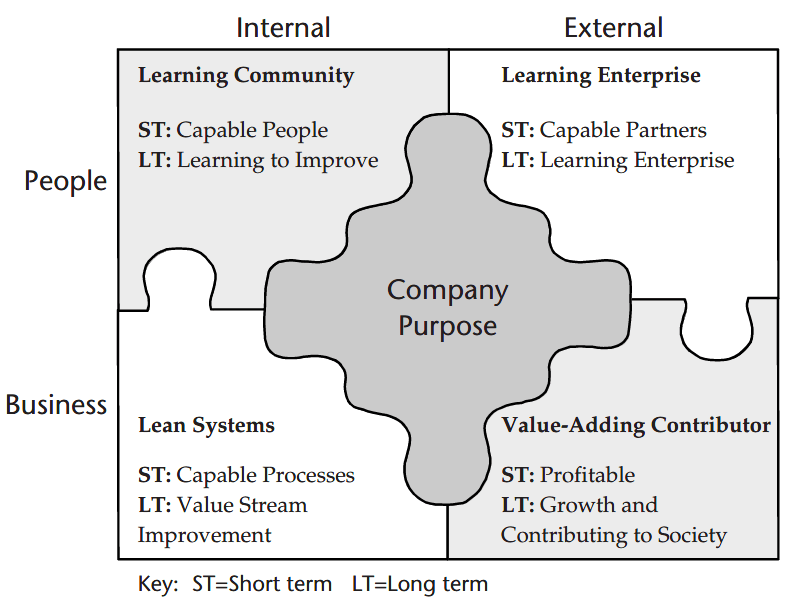

Figure 2-1. Defining the company purpose

Figure 2-1 represents company purpose as a matrix combining internal and external goals as they relate to people and business. It includes simple statements based on Toyota’s purpose and shows both the short-term goal and the longer term purpose of the company.

The short-term goals for each cell are what every company wants: capable internal processes, capable people who can do the work, capable partners who can do their jobs, and they want to make money. That’s pretty straightforward. More challenging is getting a sincere commitment by top management to longterm thinking. Let’s consider what long-term thinking means in each of the four cells.

Lean Systems

Let’s keep it simple and start with what most of the world knows best about Toyota—the technical part of the Toyota Production System. It reduces the time between a customer order and delivery by eliminating non-value-added waste. The result is a lean process that delivers high quality to customers at a low cost,

on time, and allows Toyota to get paid without holding enormous amounts of inventory. Similar lean processes can be found in product development, where Toyota has the fastest development times in the industry, getting updated styling and features to customers faster, with higher quality, and at a lower cost than competitors. And lean internal processes even extend throughout Toyota’s business support functions, to sales, purchasing, production engineering, and planning, though the lean processes are not as formalized as in manufacturing and product development.

What is less understood is that lean systems are not just about tools and techniques, but about philosophy. For example, it’s easy to understand how eliminating waste using lean tools will lead to immediate financial returns. But what about the necessity of creating some waste in the short term in order to eliminate waste in the long term? Consider the following scenarios:

- To treat the value-added worker as a surgeon and get him or her all the tools and parts needed to do the job without distracting the worker from value-added work may require some non-value-added Tools and parts may need to be prepared in advance in right-sized containers or kits, and a material handler might need to bring these frequently to the place where value-added work is being done.

- To reduce batch size and improve the flow of parts through the system may require changing over the tooling on a piece of equipment more frequently, incurring additional setup costs. SMED (single minute exchange of dies) procedures can dramatically reduce the setup time and cost, but many companies want to use that saved time to produce more parts, adding to overproduction instead of using the time to reduce batch

- To improve the quality and reduce the lead time of the product development process may require investing in dedicated chief engineers who run the programs but do not manage the people working on the This is an additional role beyond that of the more typical program manager role. Chief engineers have a lot of responsibility and need to be well paid.

- Improving the quality of a product launch may require involving suppliers early in the process and partnering with suppliers that are highly competent technically, thus paying more money per piece initially, rather than seeking the lowest cost commodity

In other words, it may be necessary to invest some money in the short term to get the high-quality lean processes needed to save money in the long term. And to make matters worse, it may not be easy to exactly calculate the savings attributable to a particular action that costs some money. For example, what is the benefit of producing smaller batch sizes compared to the cost of changing over more frequently?

One can calculate the labor cost, but the benefits of smaller batch size are more elusive. In fact, if one could calculate the benefits of each change piece by piece, we wouldn’t be talking about lean as a system. Therefore, lean systems are a matter of philosophy, though on the surface it seems to be a straightforward technical issue.

TRAP

Viewing Lean Systems as Piecemeal Technical Projects The tools of lean can be very powerful. For example, many companies have done one-week kaizen workshops and found they can save space, improve productivity, and get better quality all in one fell swoop—great stuff! Some companies even calculate return on investment at the end of each workshop. Unfortunately, to get a true lean system requires a connected value stream that goes beyond what is typically done in individual kaizen workshops. And some of the returns on investment are more elusive. Do not attempt to develop a lean system by justifying every improvement piecemeal. You will find the low hanging fruit but you won’t get a sustainable system that continues to drive out waste, leaving a lot of money on the table.

Learning Community

Within many parts of Toyota, TPS is referred to as the “Thinking Production System.” When Taiichi Ohno started connecting operations to eliminate the waste in and between the operations, he made a startling discovery. When processes are connected, problems become immediately visible and people have to think or the processes shut down. Once the discovery was made, it was no longer accidental. The real power of lean systems, Ohno found, is that they bring problems to the surface and force people to think.

But this has a limited impact on the company unless what individuals learn is shared with others. Reinvention is its own waste. Thus, investments must be made in learning systems in order to capture the knowledge gained in trying out countermeasures, so this knowledge can be used again. And learning creates a new standard and a new plateau to build on for further learning.

Building a learning community means having individuals with the capacity to learn. This is the basic starting point. Beyond this, a community suggests belonging, and individuals cannot belong if they are short-term labor to be fired at will as soon as there is an economic downturn. Belonging to a community suggests reciprocity: a commitment by the individual to the community, and a commitment by the community to the individual.

In fact, Toyota makes very large investments in its people, as we will further discuss in Chapter 11. For example, it takes about a three-year investment to develop a first-class engineer who can do the basic work Toyota expects. Thus, an engineer who leaves in three years is a completely lost investment. The reason for the three-year investment is that Toyota is teaching the engineer to think, solve problems, communicate, and do engineering in the Toyota Way. It is not simply a matter of learning basic technical skills.

We see that Toyota views its own people in light of the broader philosophy of the Toyota Way. This leads to long-term investments they would not otherwise make. The philosophy provides the framework in which individual actions are taken.

Lean Enterprise

The philosophy just keeps building. Since 70 to 80 percent of Toyota's vehicles are engineered and built by outside suppliers, a Toyota product is only as good as the supply base. Toyota realizes customers do not excuse it for faulty parts just because an outside supplier made them. Toyota itself is responsible. And the only way to be responsible is to ensure that suppliers have the same level of commitment to lean systems, a learning community, and the lean enterprise as Toyota does. It’s all part of the value stream—part of the system.

Therefore, Toyota makes investments in its partners that often seem to defy common sense. But consider what was learned several years ago when a plant that produced p-valves for Toyota burned down. P-valves are a critical brake system component in every car sold in the world, and Toyota had made the mistake of sourcing to one supplier and one plant. With just a three-day supply of p-valves in the supply chain after the fire, a total of 200 suppliers and affiliates had to self-organize and have p-valve production up and running before the supply ran out. Sixty-three different firms were making p-valves on their own without Toyota even asking. How much is loyalty like this worth? It allows Toyota to run a very lean supply chain with confidence that in a crisis it can mobilize vast problem-solving resources. This dramatic example illustrates the powerful strategic weapon Toyota has amassed by investing in a lean enterprise.

Value-Adding Contributor

What drives Toyota executives to get up in the morning, go to work, and make the right decisions for the long term? If their goal were to simply maximize their own personal utility, as some of the economics theories presume, they would not do the things they do. Jim Press, executive vice president and chief executive officer of Toyota Motor Sales, admitted that his total compensation was much less than his counterparts in American automobile companies. When asked why he put up with it, he said: “I get paid well. I am having a ball. I am so fortunate that I am able to do this. The purpose [of the money] is so we can reinvest in the future, so we can continue to do this . . . and to help society and to help the community.”

Coming from most people, we would just smile and say what a lovely and completely unrealistic thought. But Jim Press meant it. He believes it. And as one of the top Toyota executives in North America, he can influence an awful lot of people based on that belief.

If returning a dividend to shareholders and paying fat bonuses to key executives was the only purpose of the company, there would be no reason to strive to become a lean enterprise. There would be no reason to invest in a learning community. Even lean systems would amount to short-term cost reduction through slash-and-burn lean. So the philosophy interrelates everything. And without all of the pieces, the 4P pyramid collapses.

TIP

Developing a lean system is similar to saving money for retire- ment. Effort and sacrifice must be made in the near term in order to reap the benefit in the future. The implementation process will require the sacrifice of time and resources now for the potential gains in the future. Like investing, the key to success is to start early and to make contributions regularly.

Creating Your Philosophy

Unfortunately, simply writing down Toyota’s philosophy will not get you there. It is a bit like trying to get the benefits of Toyota Production System (TPS) by imitating a kanban system or replicating a cell you saw at a Toyota supplier. It comes to life in the Toyota Way culture. So the hard work still remains. You must develop your own philosophy.

Certainly you do not have to start from scratch. You can build on what you have learned about Toyota—a superb role model. And there are many other companies and organizations you can learn from. But just as watching a great tennis player does not make you a great tennis player, what counts is what you do and the skills you develop. It is about how you behave every day . . . and what you learn.

A starting point is to get together and take stock of the current situation. This is always the basis of any Toyota improvement process. What is our culture today? What are its roots? The principle of genchi genbutsu says you must go and see for yourself and understand the actual situation. So some legwork is required. You have to go and see and talk to employees and managers. What is our real culture? How does it match our stated philosophy? There will be a gap. There is a gap at Toyota—we suspect smaller than most.

Now, what is the future state vision? What do you want your philosophy to look like? What is your way? The four-box model in Figure 2-1 can help you focus on all the essential elements. What do you want to look like internally and externally, in terms of people and the business?

For the business, you need to think about this in the context of a broader corporate strategy. You cannot be a profitable, financially healthy business without a well-developed strategy. Just the citations to the literature on strategy would fill this book. One of the chief gurus of strategy is Michael Porter. In a Harvard Business Review article (Nov.–Dec., 1996) he posed the straightforward question: “What is strategy?” He observed:

Under pressure to improve productivity, quality, and speed, managers have embraced tools such as TQM, benchmarking, and reengineering. Dramatic operational improvements have resulted, but rarely have these gains translated into sustainable profitability. And gradually, the tools have taken the place of strategy. Operational effectiveness, although necessary to superior performance, is not sufficient, because its techniques are easy to imitate. In contrast, the essence of strategy is choosing a unique and valuable position rooted in systems of activities that are much more difficult to match.

He makes many interesting observations in this article. For example, he notes that you do not really have a strategy unless the strategy states what you will not do. What are profitable business ventures you would pass on because they do not fit your strategy? If the answer is none, you do not have a strategy, according to Porter. He also talks about systems of activities that translate the strategy into action, and an alignment of the systems of activity with the strategy— something that is very visible in Toyota’s system.

If you have a great strategy that defines how you will be a unique valueadding contributor, you need to fill in the other three boxes. These speak to Porter’s “systems of activities.” To achieve this strategic vision for the business, what does operational excellence look like? That is, what lean systems are required to satisfy the outside business purpose? What kinds of people are needed to support this vision inside the company and in your partners? The totality of the answers to these questions will define the philosophy of your company.

Going off-site and getting top leadership to agree on your way is a great start and certainly worth doing. You should do some groundwork to look at your current state. You should look back in history at your company’s heritage and what has shaped your culture. But having come out of such an off-site meeting with a feeling of renewal and a commitment to a grand vision is just the starting point.

Living Your Philosophy

The preface to The Toyota Way quotes Mr. Cho, who was president of Toyota and an Ohno disciple:

What is important is having all the elements together as a system. It must be practiced every day in a very consistent manner—not in spurts.

How could he be so cruel as to raise the bar so high? Turning a philosophy into practice in spurts is tough enough, but making it so natural that it’s practiced consistently every day can seem downright impossible.

To make matters worse, the responsibility for living the philosophy falls straight on the shoulders of a particular and easily identifiable group: leadership. All executives, managers, directors, supervisors, group leaders, or whatever else you call them have to live the philosophy “every day in a very consistent manner.” Leaders have to lead by example . . . consistently.

To do this requires a major commitment, starting from the very top of the company. It is not just an abstract philosophical commitment to support “lean.” It is a commitment to a “way”—a way of looking at the business purpose, of looking at processes, of looking at people, and a way forward in learning to learn as an organization.

The various commitments that leaders must be prepared to make are summarized in the 4P model in Figure 2-2, below. We show the Toyota Way management principles as a set of leadership commitments essential to moving forward in learning from the Toyota Way. Each of the management principles is associated with a philosophy—a way of thinking about purpose, process, people, and problem solving. When President Cho issued the “Toyota Way 2001” as an internal document, he was reinforcing the needed commitment of all leaders. Toyota then proceeded to develop a comprehensive training program to help leaders think in the Toyota Way. The training includes detailed case studies where managers critique a plant manager’s approach to a plant launch based on all of the Toyota Way principles. It includes managers leading projects to improve processes using appropriate Toyota Way methods. No manager is exempt. It takes about six months, and it is one small part of reinforcing commitment to the Toyota Way.

Making a Social Pact with Employees and Partners

On the people side, if this is to be a community of learning together for the long term, then some long-term agreements need to be made. In Japan there is much less reliance on formal documents and litigation than we see in the United States. In Japan face-to-face meetings, word of mouth, and basic understandings between people play a larger role in commerce. Toyota has never written down an employment guarantee or a guarantee that suppliers will retain the business if they are doing a good job. But there is certainly a strong and well-understood social pact.

The social pact was clarified in 1948 when Toyota Motor Company president and founder Kiichiro Toyoda resigned. The Japanese economy was in terrible shape, and Toyota’s debt was eight times its capital. Kiichiro tried to solve the problem with voluntary wage concessions but concluded that he needed to lay off 1,600 workers to keep the company afloat. But he did it in an unusual way. He personally took responsibility and resigned first. He then got agreements from 1,600 workers to voluntarily “retire.” This was very painful for the company, but the Toyota leadership vowed at the time never to get into that dire situation again. This is one reason why Toyota is such a fiscally conservative company, with tens of billions of dollars in cash reserves.

Problem Solving (Continuous Improvement and Learning)

Commitment to building a learning organization

Commitment to understanding process in detail

Commitment to thorough consideration in decision making

People and Partners (Respect, Challenge, and Grow Them)

Commitment to developing leaders who live the philosophy

Commitment to developing people and partners for the long term

Process (Eliminate Waste)

Commitment to lean methods for waste elimination

Commitment to value stream perspective

Commitment to developing excellent processes supported by thoroughly tested technology

Philosophy (Long-Term Thinking)

Commitment to long-term contributions to society

Commitment to company economic performance and growth

Figure 2-2. Top leadership commitment required

In The Toyota Way you will find the example of TABC in Long Beach, California, which was set up to make truck beds in 1972. In 2002, Toyota decided to move truck bed production to a new plant in Mexico. Cheaper labor you assume? Go to the Web page for TABC and you find that “in 2004, when truck bed production shifts to TMMBC, TABC will assemble commercial trucks for Hino Motors to be sold in North America, and beginning in 2005, TABC will assemble fourcylinder engines.” Since that was written, it in fact happened. TABC is alive and there were no layoffs. There were a variety of reasons to move truck bed production to Mexico, but Toyota would not close down TABC and fire the workers who had done a good job for the company.

The commitment is clear: Toyota will not lay off employees who are doing good work for the company except as a last resort to save the company. Employees who are not performing get warnings and must show that they are seriously trying to improve.

Like all companies, Toyota deals with ups and downs in the marketplace. They use flexible staffing as a shock absorber. First, they have considerable numbers of “temporary workers” from contract companies. This can be 20 percent of the workforce. They do not have the same commitment to temporary workers as they do to regular workers. But they do have long-term relationships with the contract labor companies who understand their requirements, and Toyota gives these outside partners steady business. They also have affiliated companies in the broader Toyota group and can add and subtract labor through transfers of personnel.

The question for your company is very simple: What type of social pact will you make with your employees? Again, start with your historical understanding, which may be just fine as is. But if the reality is that employees are added and subtracted at will based on market conditions and simple ROI calculations on plant closings, something will have to give. Either change the pact or forget about becoming a lean learning enterprise in the true sense.

Maintaining Continuity of Purpose

A number of major corporations have made significant progress on the lean journey. It typically starts when someone with operational responsibility—a vice president or even a middle manager—decides to seriously investigate what lean can do for the company’s operations. It’s often driven by a real business concern, such as shrinking margins forcing severe cost reduction, or it can be opportunities to expand the business and a desire to minimize major capital investments. Consultants are brought in, someone is assigned to lead the lean initiative, lo and behold, it works! It works in the sense that processes are improved, material flows better, and the needle on performance indicators moves—at least for the areas where lean is applied.

Success motivates, and there is nothing better than achieving the business objective. This can lead down several paths. One is to spread lean and strive to get even more of the good results. Teach more employees the lean tools, and find more projects. Companies that have done this find that they keep on getting improvements here or there but at some point realize it is not coming together as a system. They also realize that the gains are not sustained and technical changes are slipping back to the old way of doing things. To make it come together as a sustainable system requires another major leap forward. Top management must realize that lean is more than a set of tools and techniques. It is a way of thinking about the very process of management.

Companies that have made this next big leap forward from tools and techniques to a management philosophy and a system start shifting attention to culture change. What do we mean by culture? It is a shared set of values, beliefs, and assumptions. The key is that it is shared. And strong cultures last beyond particular leaders. Constancy of purpose comes from having a strong company culture starting at the top leadership level, and sticking with it across generations of leaders. Arguably, Toyota’s basic management culture began when Sakichi Toyoda started Toyoda Automatic Loom Works in 1926. Since then, the management principles of the Toyota Way have evolved, but have not deviated in any fundamental way from what Sakichi believed. We are talking about almost 80 years of an evolving culture—of constancy of purpose. In historical terms that still is a tiny slice of time. But it beats most companies that turn over leadership every one to three years, and with each new leader comes a new philosophy.

So how can you get what Edward Deming called “constancy of purpose”?

The answer is simply that it has to come through continuity of leaders. You need a set of aligned leaders who truly believe in a common vision for the company. You need to act on it in a consistent way over time. Eventually, if you do this, it will become your culture. Then, to keep the culture going, leaders who live the culture must be grown from within. This requires a succession system. Any leaders brought in from the outside have to start somewhere below the top of the company and be carefully developed and nurtured over years in your way.

What if you do not have committed leaders? You have to start someplace. And the best place to start is through actions that improve processes and deliver bottom-line results. Use that to gain management attention and start building support from the grass roots level up. If you do not succeed in changing the thinking of top leaders at least you will have some improved processes, and you will have learned a lot.

TRAP

Faking a Valiant Purpose

Many companies have off-site meetings where they proclaim motherhood and apple pie mission statements—satisfying customers, empowering employees, continuous improvement, and on and on. While a good first step, the second step is to take the mission statement seriously. Behavior that is contrary to the mission statement immediately signals to the ever weary employee that the commitment is not real. Credibility is lost and the mission statement is worthless . . . actually doing more harm than good to morale.

Reflection Questions

Gather statements of your company’s values (Hint: The mission statement is one source).

Evaluate the relationship between stated values, beliefs, mission, and what the company actually seems to stand Consider the model in Figure 2.1. Evaluate your company’s values and mission in light of this model.

- Is the purpose of your company narrowly stated in one of the four boxes, or across all the boxes—internal, external, people, and business?

- Do you have a clear and consistent social pact with team associates?

- Are team associates partners or variable costs?

- Does the company philosophy change with each CEO or is there continuity of purpose?

Take the opportunity in an off-site meeting, or arrange an off-site meeting, to discuss and write down your company’s way. It should build on the strengths and unique history of your company.

Begin the process of educating all your leaders on your company’s way.