The second overarching question mentioned in the introduction to Toyota Kata is: How can other companies develop similar routines and thinking in their organizations? At this point we have a basic awareness of what Toyota is doing to achieve continuous improvement and adaptiveness, as described in Parts III and IV. There is, of course, more to learn there, but we would perhaps do well to shift some of our attention away from the question of what Toyota is doing and more onto that second question. While it is interesting to study and discuss Toyota, even more important may be the experimentation, learning, and development we do for ourselves in our own situations.

Be Clear About What You Are Undertaking

Some other ways to phrase the second overarching question might be:

How do we get everyone in the organization to think and act along the lines of the improvement kata described in Planning: Establishing a Target Condition and Problem Solving and Adapting: Moving Toward a Target Condition?

How do we get this behavior routine into an organization?

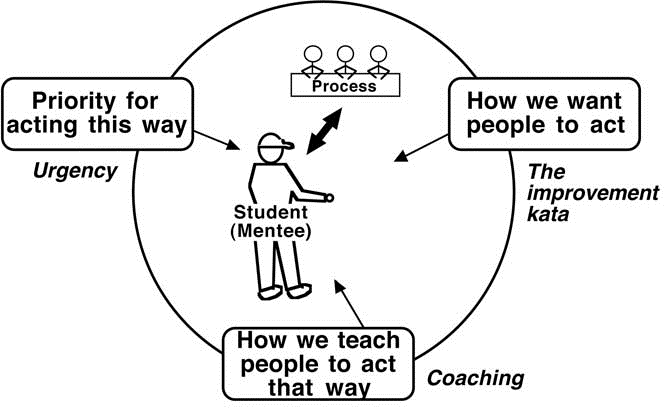

Figure 9-1. The task

How do we spread improvement kata behavior across the company so it is used by everyone, at every process, every day?

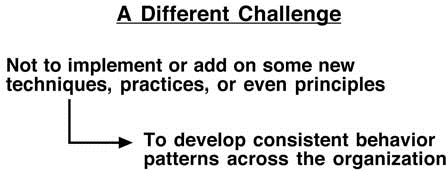

How do we learn a new way of thinking and acting?

Which is to say that before we go any further, we should be clear about the challenge. Knowing about the improvement kata that lies behind Toyota’s success, and that it is about behavior patterns and developing such behavior patterns, ask yourself: Is this what you intend to do? Developing new behavior patterns across an organization involves a more significant effort and further-reaching change—particularly in leader behavior—than what you may have assumed that “lean manufacturing” is about. It should be clear to you at this point that bringing continuous improvement into an organization—“lean” or the “Toyota Production System”—involves a different kind of challenge than we originally thought. Toyota’s embedding of the improvement kata and the coaching kata into daily work represents more than just adding something on top of our existing way of managing. It means changing how we manage (Figure 9-1).

Organization Culture

Trying to get each person in an organization to think and act in certain ways means you are working on organization culture. Most organizations that are interested in Toyota’s approach probably do not need to completely change their existing culture, but rather, to make an adjustment, like maneuvering a curve in the road, as shown in Figure 9-2. So how does one make such a change in organization culture?

Figure 9-2. Making a shift in organizational culture

What Do We Know So Far About This Challenge?

Since the late 1980s, Toyota has successfully—though not without difficulty—been spreading its approach to local citizens at new Toyota Group sites around the world; that is, inside Toyota. This includes North America and Europe, and it suggests that Toyota’s improvement kata should be practicable for organizations and people outside of Toyota. However, in Chapter 1, I stated the following:

To date, it appears that no company outside of the Toyota group of companies has been able to keep improving its quality and cost competitiveness as systematically, as effectively, and as continuously as Toyota.

Astute readers may have already been wondering as they started this chapter: “If no company outside Toyota has succeeded in bringing such systematic continuous improvement into all processes every day across the organization, then how can anyone answer the question being raised at the beginning of this chapter and tell us how to do it?”

The fact is we simply do not yet have authoritative answers to the second overarching question, and that includes Toyota itself too. For example, Toyota’s efforts to spread its approach to its outside suppliers have achieved many point successes in a wide variety of processes and value streams, but even those efforts to integrate the improvement kata into everyday operation across the organization at these other companies have so far not met expectations.

What I can do in this chapter is share with you what we have learned with regard to the second overarching question—which in fact is quite a lot—and how we are working on issues raised by that question.

You Need to Become an Experimenter

The goal of this chapter—and this book overall—is to set you up to experiment and thereby develop your management system in accordance with the needs of your situation. If you want to change behavior patterns and organizational culture, then it is quite likely there is no other way:

- There is probably no approach that fits all Each company should work out the details by developing its management system to suit its particular situation.

- There is great value in striving to understand the reality of your own situation and experimenting, because it is where you No one can provide you with a solution, because the way to answering the second overarching question—as with any challenging target condition—is and should be a gray zone.

But we do know how to work though that gray zone. The improvement kata, the means by which processes are improved, is a way of experimenting, and we can apply it to almost any sort of process. So when I say you need to become an experimenter, it does not mean that you have to start a separate activity. We can continuously improve and adapt, train people, and develop our organization culture simultaneously, with the same activity. In fact, this describes quite well how Toyota goes about it.

There is now a growing community of organizations that are working on this, whose senior leaders recognize that Toyota’s approach is more about working to change people’s behavior patterns than about implementing techniques, practices, or principles. In fact, as you strive to develop improvement kata behavior and thinking in your organization, that step-by-step effort will have an effect on your techniques, practices, and principles. That is a good way to look at it.

What Will Not Work

Some of the early lessons from our experimentation were about approaches that do not work for changing people’s behavior. Let us get those out of the way from the start. If you wish to spread an improvement kata (a new behavior pattern) across your organization, then the following tactics will not be effective:

- Classroom Even if it incorporates exercises and simulations, classroom training will not change people’s behavior. It seems for several years now we have assumed that simply comprehending Toyota’s system would automatically lead to its adoption—because it makes sense! This approach has been decidedly ineffective. Intellectual knowledge alone generally does not lead to change in behavior, habits, or culture. Ask any smoker.

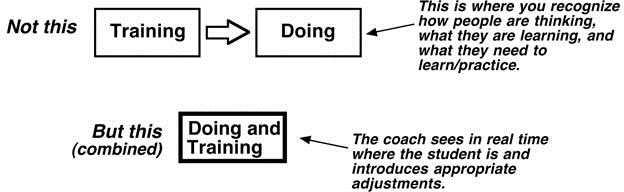

As mentioned in Toyota Coaching Kata: Leaders as Teachers, the concept of training in sports is quite different from what “training” has come to mean in our companies. In sport it means repeatedly practicing an actual activity under the guidance of a coach. That kind of training, if applied as part of an overall strategy to develop new behavior patterns, is effective for changing behavior.

Classroom training has a role, but the best that we can probably achieve with it is awareness. And even that tends to fade quickly if it is not soon followed by repeated, structured practicing. Classroom training should probably be kept short and provided mostly for information purposes and to participants who are about to go into hands-on practicing with a coach.

- These are designed to make point improvements, not to develop new behaviors. Furthermore, as discussed in Chapter 2, results naturally tend to slip back after a workshop ends.

- Having consultants do it for Developing internal routines and capability for daily continuous improvement and adaptation at all processes involving all people—culture—is by definition something that an organization must do for itself. An experienced external consultant can provide coaching inputs, especially at the beginning, and even experiment together with you. But to develop your own capability, the effort will have to be internally led, from the top. If the top does not change behavior and lead, then the organization will not change either. More on that later in this chapter.

- Looking to metrics, incentives, and motivators to bring the desired As we have discussed, there is no combination of metrics and incentive systems that by themselves will generate improvement kata behavior and change your culture to one like Toyota’s.

- Many companies have tried unsuccessfully to reorganize in the hope of finding organizational structures that will stimulate continuous improvement and adaptiveness; for example by bringing departmental functions into value-streamoriented organizational structures.

As tempting as it sometimes seems, you cannot reorganize your way to continuous improvement and adaptiveness. What is decisive is not the form of the organization, but how people act and react. The roots of Toyota’s success lie not in its organizational structures, but in developing capability and habits in its people. It surprises many people, in fact, to find that Toyota is largely organized in a traditional, functional-department style.

Anything unique about Toyota’s organizational structures, such as their team leader approach, evolved out of Toyota striving for specific behavior patterns, not the other way around. First figure out how you want people to act—for example, along the lines of the improvement kata—and strive to develop those behavior routines. If, then, along the way, making organizational

adjustments is a necessary or useful countermeasure, that’s okay. But these should be seen for what they are: countermeasures, not target conditions. Keep your attention on the target condition of developing improvement kata behavior, and let the needs of your efforts there drive the evolution of your structures.

All these tactics have their place, but they will not generate improvement kata behavior, nor the cost, quality, and adaptiveness benefits that accrue from daily application of that kata. Culture change is not achieved through books, intellect, classroom training, discussions, or anything similar.

How Do We Change?

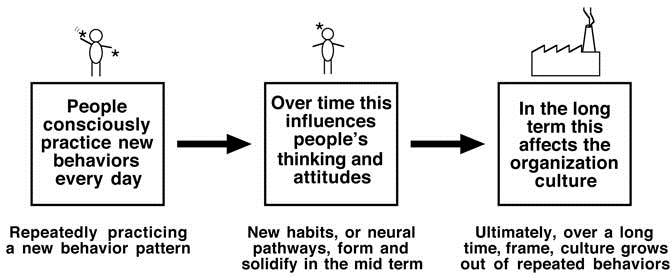

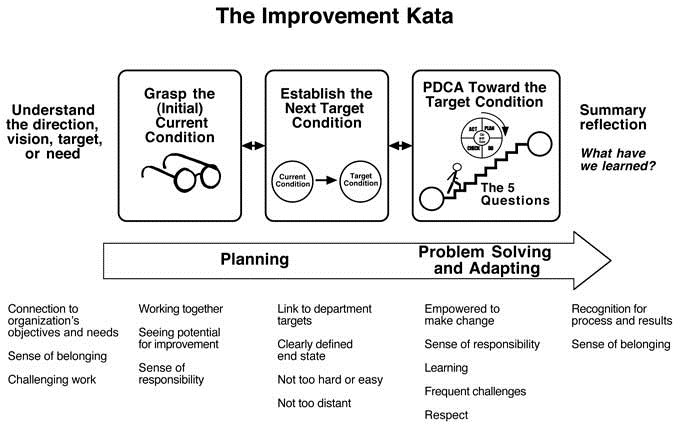

The field of psychology is clear on this: we learn habits, automatic reactions, by repeatdly practicing behaviors. In order to build new mental circuits, we must practice a desired behavior pattern and periodically derive a sense of achievement from that behavior. The canon that we learn by doing, by experiencing, has given rise to the wellknown and widely accepted change model depicted in Figure 9-3.

Much of what we do is routinized and habitual. Repeated practice—conditioning—creates neural pathways and, over time, an organization’s culture. This change model is particularly important with regard to the improvement kata because several aspects of that kata are so different, and even counterintuitive, from the perspective of our current management approach. The only way to truly understand its underlying meaning and learn to apply it in different situations is by personally and repeatedly practicing it in actual application.

Figure 9-3. A model for changing organization culture

Ideally, following the improvement kata pattern would become automatic and reflexive, and our mindfulness thereby freed to be applied to the details of the situation at hand. This is the ideal that Toyota’s coaching kata, described in Chapter 8, strives to achieve, and a reason why Toyota people have had difficulty explaining to us the underlying pattern of what they do.

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.

To know and not to do is not yet to know.

—Aristotle

—Zen saying

Fortunately, kata are designed specifically for passing on. In martial arts, kata were apparently created so the masters could pass on their most effective fighting techniques to further generations. In other words, kata are a way of doing exactly what we are discussing here: practicing behaviors and learning new habitual routines.

How to Experiment

Use Actual Work Processes

This is something we adopted one-to-one from Toyota’s approach: training and doing are not separated (Figure 9-4). To practice the improvement and coaching katas, students apply them in actual situations at actual work processes. In this manner your experimentation will be real, not theoretical. You can perceive where the student truly is with his thinking and skills, and take appropriate next steps. And the degree or lack of improvement in the processes serves as a metric for the effectiveness of your effort to coach and develop the desired behavior routines.

Figure 9-4. Experimenting with real processes

Focus On Three Main Factors

If we want to get people, including ourselves, to think and proceed along the lines of the improvement kata, I propose three main factors that we can influence in order to achieve this (Figure 9-5).1

Focusing on any one of these three areas alone is not effective for changing to a desired organization culture, and conversely, if any one of them is left out, the effort is also not effective. For instance, just

Figure 9-5. Three factors that we can influence

establishing urgency for change typically generates a wide range of behavior reactions. The result is often no real change at all or something quite different from the improvement kata. We should not expect that simply pushing people will generate improvement-kata behavior.

Likewise, coaching alone achieves very little. Coaching in what?

Finally, just defining and explaining the improvement kata, even if we were to combine that with a sense of urgency, will also not change people’s behavior. It would be like saying to an athletic team, “You should play this way in order to win,” and then leaving the team alone.

Use the Improvement Kata to Develop Improvement Kata Behavior

This is the most important advice in this chapter: to develop improvement kata behavior in your organization, you should utilize and follow the improvement kata in this development process itself. Simply put, the improvement kata is your means for experimenting.

This is not about “implementing” a new management system and culture. The way to any target condition, including culture change, is unclear, and practicing good PDCA will be a key factor in successfully achieving that condition. In other words, while working toward a target condition that includes a changed culture, it is just as important to frequently check the current condition and adjust accordingly. Developing new behavior patterns is a change process that occurs over time via PDCA.

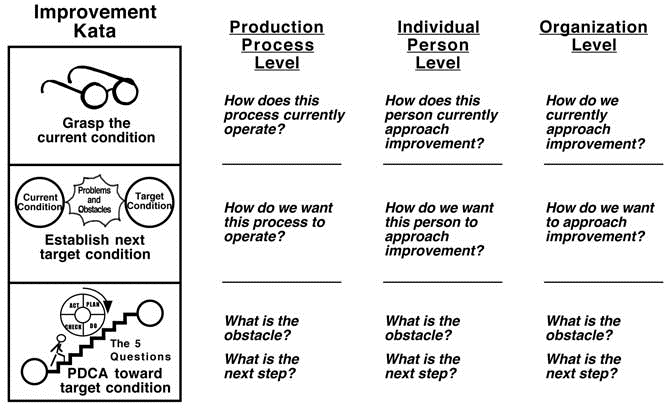

Using the improvement kata in order to introduce improvement kata behavior is an example of applying it at a higher fractal level than at a production process. The improvement kata can be used at all levels, and anyone in the organization can be asked the five questions (Figure 9-6).

Let us take a closer look at how this can be done. As described in Part III, the improvement kata is applied to a work process by:

- Grasping the current condition

- Defining a measurable target condition

Figure 9-6. The improvement kata finds application at all levels

- Utilizing short PDCA cycles to move toward that target condition

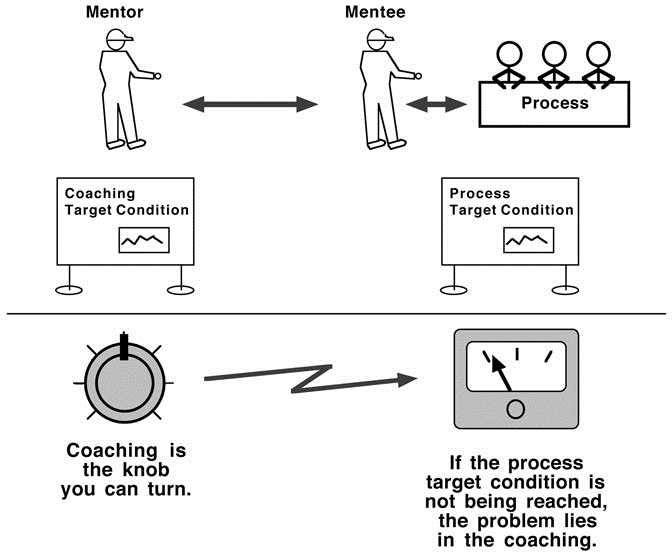

The point to realize is that precisely the same kata can be applied to a coaching process. A target condition can be established for coaching, and you can PDCA toward that target condition.

A baseline assumption we should make here is that the improvement kata works. In other words, our experimenting is not done in order to test if the improvement kata is effective, but to learn what we need to do in order to develop effective improvement kata behavior. Ergo, if the improvement kata is not yet operating as desired, then it is the teaching/coaching of it that needs to be adjusted via PDCA. As shown in Figure 9-7, our coaching approach is perhaps the main knob we can adjust in order to develop desired behavior patterns. If you do not like the results at the work process, then scrutinize the coaching. In this regard, I encourage you to keep in mind: “If the learner hasn’t learned, the teacher hasn’t taught.”

Figure 9-7. If the improvement kata is not working properly, the coaching needs adjusting

Tactics

The remainder of this chapter describes specific tactics I have been using, which may be generic enough to be applicable at other organizations. Since a discussion of tactics is essentially a discussion of solutions (countermeasures), I urge you to view them as thought starters, ideas and inputs to your own efforts to develop improvement kata behavior in your organization. It would not be appropriate or effective for me to propose countermeasures without understanding your specific current and target conditions, nor for you to jump directly into applying someone else’s countermeasures. Again, the best advice here is to utilize and follow the improvement kata routine as you try to develop the improvement kata routine in your organization. Then you can adapt to what you are learning in your situation and find your own appropriate path to the desired condition.

Learning to Do Before Learning to Coach

Coaches should be in a position to evaluate what their students are doing and give good advice; to bring their students into the corridor of thinking and acting prescribed by the improvement kata. In other words, coaches should be experienced. It is only after they have practiced improvement kata themselves that coaches will be able to see deeply enough to provide that useful advice.

If a coach or leader does not know from personal experience how to grasp the current condition at a production process, establish an appropriately challenging target condition, and then work step by step toward that target condition, then she is simply not in a position to lead and teach others. All she will be able to say in response to a student’s proposal is, “Okay” or “Good job!” which is not coaching or teaching. The catch-22 is that at the outset there are not enough people in the organization who have enough experience with the improvement kata to function as coaches. This is not unlike Toyota’s problem as it grows rapidly. It will be imperative to develop at least a few coaches as early as

possible. (See “Establishing an Advance Group” later in the chapter.)

Who Practices First?

At Toyota, the improvement kata is for everyone in the organization and everyone practices it. No one group is singled out. However, Toyota is not trying to change its kata; it is continuing with the same basic approach it has been following since the 1950s.

On the other hand, if an organization wishes to effect a change in culture rather than continuing on the same path, it requires leadership from one group in particular: the senior level. In such a change situation, the senior managers should practice the improvement kata ahead of others in the organization.

Managers and leaders at the middle and lower levels of the organization are the people who will ultimately coach the change to the improvement kata, yet they will generally and understandably not set out in such a new direction on their own. They will wait to see, based on the actions (not the words) of senior management, what truly is the priority and what really is going to happen.

George Koenigsaecker, an early lean thinker in the United States, has depicted this effect using the normal distribution curve.

What Mr. Koenigsaecker’s diagram suggests is that only a small percentage of people in the organization (the right tail of the curve) will welcome a change effort and actively participate. Another small group (the left tail) will fight it actively. And the great majority—although they may nod and indicate their support—will be on the fence and waiting to see what is going to happen. Although many have criticized mid-level management for avoiding change, if you think about it, the wait-and-see attitude is an understandable reaction to uncertainty by managers who are on a career ladder in an organization. Also, do you want your managers to easily jump from one way of managing to another?

The point is:

- The way the majority of managers and leaders behave—the people in the middle of the normal curve—will determine how people in the organization act, and thus determine the organization’s

- If the senior managers do not go first in personally practicing and learning the improvement kata, then it is unlikely that they will be able to effectively enlist, mobilize, and guide those managers and leaders toward the desired behavior The kind of cultural shift we are talking about cannot be delegated by the senior leaders.

Establishing an Advance Group

Before starting to teach senior managers the improvement kata, we have tended to first establish a small advance group. The initial purpose if this group is to develop familiarity with the subject and how it works. It is this advance group that actually goes first with practicing the improvement kata.

I include a senior executive—the senior executive in the case of small and mid-sized companies—as a member of this group. The advance group is not a staff group or lean manufacturing department that will be responsible for all mentoring and training, or for making improvement happen at the process level. That will be the responsibility of the local managers and leaders at each level and in each area in the organization. Do not create a lean department or group and relegate the responsibility for developing improvement-kata behavior to it. Such a parallel staff group will be powerless to effect change, and this approach has been proven ineffective in abundance. Use of this tactic often indicates delegation of responsibility and lack of commitment at the senior level.

The advance group is responsible for monitoring, fine-tuning, and further developing (via PDCA) the organization’s teaching approach. The advance group is the organization’s “keepers of the kata,” so to speak. However, this group will to some degree also assist with coaching at all levels of the organization so that it can maintain a grasp of the true current situation in the organization.

To be a workable size, the initial advance group should consist of no more than about five people. This group needs a mentor—for example, an external consultant. If you utilize an outside coach, it is important that you hire this coach specifically to help you get started and develop your internal coaching capability. Do not hire an external person to do the coaching work for you, because then you will not build this important capability in your organization. An external coach’s job is to accelerate and help guide the development of your capability.

A good first step for the advance group is to simply try applying the improvement kata to a few assembly processes, all the while reflecting: “What are we learning about the improvement kata, our processes, our people, and our organization?” This allows the group to develop a better understanding of what the improvement kata

entails and to simultaneously gain a firsthand grasp of the current condition at the process level in the organization. A good place to begin practicing the improvement kata is at a “pacemaker process.” Appendices 1 and 2 explain what that is and provide detail for assessing the current condition of a production process, which is the beginning of the improvement kata and prerequisite for establishing a target condition.

Something this group can do immediately, for instance, is to assess the stability of a production process, as described in Chapter 5. This involves timing and graphing 20 to 40 successive cycles at several points in the process and then asking, “What is preventing this process and the operators from being able to work with a stable cycle?”

These initial efforts to try out the improvement kata can easily occupy the advance group for two to six months. That may sound like a long time, but consider that we are talking about how we want the organization to operate; its culture. The advance group should not go into this task with only a shallow understanding of what is involved and where the organization is.

These initial shop-floor activities of the advance group are also a good opportunity to get started in training your first few internal coaches. We have tended to attach two or three potential coaches to the advance group, in addition to the four to five advance group members. These coaches in training do not participate in all advance group activities, such as planning activities. They participate in the shop-floor efforts to apply and learn about the improvement kata.

Training Through Frequent Coaching Cycles and the Five Questions

To develop new habits, the field of psychology tells us it is preferable to practice behaviors for a short time frequently—such as every day— rather than in longer sessions but less frequently. Ideally, of course,

every encounter and interaction in the organization would radiate the kata, as in the mentor/mentee case example in Leaders as Teachers.

To get people to frequently practice and think about the routine of the improvement kata, I currently use a concept I call a “coaching cycle.” These cycles come into play after a process target condition has been established, and utilize the five questions. The five questions are a regimen to train improvement-kata behavior. They simplify a part of the improvement-kata routine and thus make it easier to apply, understand, and transfer. One coaching cycle essentially entails the mentor going through the five questions once while standing at the process with the mentee (Figure 9-9). In most cases, we have been striving to do this at each focus process at least once per shift. The purpose of a coaching cycle is:

The Five Questions Make Up One Coaching Cycle

- What is the target condition? (The challenge)

- What do we expect to be happening?

- What is the actual condition now?

- Is the description of the current condition measurable?

- What did we learn from the last step?

- Go and see for yourself. Do not rely on

- What problems or obstacles are now preventing you from reaching the target condition?

Which one are you addressing now?

- Observe the process or situation

- Focus on one problem or obstacle at a

- Avoid Pareto paralysis: Do not worry too much about finding the biggest problem right If you are moving ahead in fast cycles, you will find it soon.

- What is your next step? (Start of next PDCA cycle)

- Take only one step at a time, but do so in rapid

- The next step does not have to be the most beneficial,

biggest, or most important. Most important is that you take a step.

- Many next steps are further analysis, not

- If next step is more analysis, what do we expect to learn?

- If next step is a countermeasure, what do we expect to happen?

- When can we go and see what we have learned from taking that step?

- As soon as possible. Today is not too How about we go and take that step now? (Strive for rapid cycles!)

Figure 9-9. Contents of a coaching cycle

- To allow the coach to quickly grasp the current condition in both the process being improved and the mentee so that the coach can judge what is an appropriate next step

- To provide a routine for conditioning training

- To recognize the mentee’s efforts

With practice and experience, one coaching cycle should not take very long. Novice coaches sometimes mistakenly let the cycle get into lengthy discussions that cover many different factors and can run into hours. I have been shooting for 15 minutes per coaching cycle in many cases. As soon as a single next step—not a list of steps—is clear to both mentor and mentee, then the coaching cycle is over. As in the mentor/mentee case example, the next step can and often should be very small. That is perfectly acceptable, as long as the cycles are rapid. A coaching cycle is not all there is to coaching, of course. Get through the five questions one time relatively quickly and take stock: “What is the situation now? Where are we in the improvement kata, in the process being improved, and in the development of this person’s capabilities? What is needed next?” After a coaching cycle, the mentor can then, for example, decide whether he should stay on with the mentee during the next step—to observe and provide guidance as Tina did in the mentor/mentee case example in Chapter 8—or return later for a check by means of another coaching cycle. The next coaching cycle should follow as soon as possible, often within hours or even minutes on the same day. If the next step can be taken right away, then by all means do that.

A few lessons learned about coaching cycles:

- It is a good idea to limit a student’s first few target conditions to a time horizon of only one week. This way, the student can get more experience with the entire improvement kata, experience some success, and begin to develop a After some practice you can begin to lengthen the target condition horizon a bit to, say, one to four weeks out.

- Do not wait until the end of a shift to conduct coaching Think of a check as a beginning, not an end, and do it early in the workday if possible. You can specify the time of day as part of a coaching target condition. If we’re always putting off coaching cycles until the end of the workday, it suggests the lack of a specific coaching target condition and a low level of priority.

- Whenever you approach any process, go through the five questions. In this manner you will not only be teaching others the way of thinking, but you’ll be teaching yourself as

- The fifth question—“When can we go and see what we have learned from taking that step?”—has been a sticking point. New coaches often ask this question thinking that the next step must be a countermeasure or solution. Likewise, the mentee often thinks this is what the coach wants. In many (or even most) cases, however, the next step is just to get a deeper grasp of the situation, as was illustrated in the case example in Chapter

- Another lesson is to coach only one target condition at a time, which generally means one mentee at a If you try to coach several mentees at once, the dialogue tends to become too general and mentees may become less open about discussing problems. Every mentee is potentially in a unique situation and usually has unique development needs.

Sense of Achievement

Developing a new mindset also involves periodically deriving a feeling of success from practicing the behavior patterns. While we may think that success only comes at the end of something, there are important opportunities for positive reinforcement at all stages of the improvement kata, as shown in Figure 9-10. These opportunities should be utilized, since the objective is not just solutions, but building the capability to follow the improvement kata routine, to understand situations and develop appropriate solutions.

Figure 9-10. Example opportunities for successes throughout the improvement kata routine

Making a Plan

Once the advance group has spent a few months learning by applying the improvement kata at some processes, there will be a need for a plan to begin wider development of improvement kata behavior. The time horizon for such a first plan should not exceed 12 months, since at this stage you are on a steep learning curve and your grasp of conditions is likely to change appreciably. Because of our limited experience, our flashlight does not shine very far ahead.

Creating such a plan is the same as any A3 planning process as discussed at the end of Chapter 8:

- The advance group needs a mentor to whom it will present its planning efforts iteratively in coaching In developing this plan, the group focuses on one section heading at a time, since one section sets the framework for the next. Until the plan is signed, however, it is acceptable to go back and make adjustments to prior sections.

- Much of the benefit of the plan lies in the iterative planning process, because it forces you to get facts and data and repeatedly think through—deeper and deeper each cycle—what you are doing. The objective is not just to have a plan, but to go through the step-by-step effort to create the

- It takes time to develop this kind of plan, easily two months. Continue practicing the improvement kata and testing ideas while the plan is being developed, since this helps you stay close to the real

The following key points for this planning process are presented under their respective A3 headings.

1. Theme

The theme is to develop the behavior of managers and leaders toward a pattern that follows the improvement kata. However, be sure to keep the theme and activities linked to continuous improvement of production processes, since cost reduction via process improvement is the overall objective. We are not introducing the improvement kata for the sake of introducing the improvement kata. We should be improving processes and practicing (learning) the routine of the improvement kata simultaneously.

As described in Chapter 3, Toyota’s improvement kata functions within an overall sense of direction, which is provided by a long-term vision. Without this you will find people going off in several directions when they hit obstacles. Thus, one of the first questions to ask yourself is, “Do we have consensus on a vision, that is, a long-term direction?” I have witnessed several groups that went into long intellectual discussions about establishing a vision, and they typically ended up producing useless statements that protect several people’s sacred cows. Developing a succinct, useful, but not overly confining long-term vision is difficult. It takes a considerable amount of time and reflection, and is not necessarily a democratic process. Also, if we are just beginners with understanding the potential of the improvement kata, then perhaps this is not yet the right time to be arguing about what might be an appropriate vision.

But you do need a vision, and if you are a manufacturer I see no reason why you should not simply adopt the same long-term vision for your production operations that Toyota strives for: “One piece flow at lowest possible cost.” As we have seen in Chapter 3, this vision does not come from Toyota or Japan, and has been pursued for a few hundred years. Why not adopt this widely recognized production vision and get going?

2. Current Condition

The advance group has been gaining firsthand understanding of the current situation by trying to apply the improvement kata at the process level in the organization. Summarize what is being learned in bullet points. This summary should at least describe a) the current behavior of managers and leaders, and b) how process improvement is currently handled. You can also include any additional factors you would like. Some aspect(s) of this description of the current condition should be measurable so that you can gauge if you are making progress. (More on metrics later in this plan.)

Based on what the advance group has learned by immersing itself in the current condition, it can then establish a target condition.

3. Target Condition

What you are defining here is a condition you want to have in place at a future point in time (such as 6 or 12 months from now). Defining this takes some time and iterations, because it should be based on facts and data, and be specific and measurable.

There are two aspects to the target condition in this section of the plan:

- Relative to process improvement For example:

- Total number of processes being managed and improved via the improvement kata

- Measurable process improvement, such as process stability

- Relative to leader/coaching For example:

- What persons will have reached what capability level (Figure 9-11)

- What persons will be carrying out the improvement kata and the coaching kata, at what frequency, and at how many processes

How you intend to get to this target condition will be the subject of the next section of the plan.

Keep in mind as you define the total number of processes that, because the improvement kata is an approach for daily management, once you begin with the improvement kata at a process there is no end there. This means that, unlike improvement projects or workshops that have an end date, the number of processes being improved through the improvement kata accumulates and grows as you spread the approach to other processes. Do not overextend yourself at the start. In the beginning it is better to have picked too few focus processes, rather than too many.

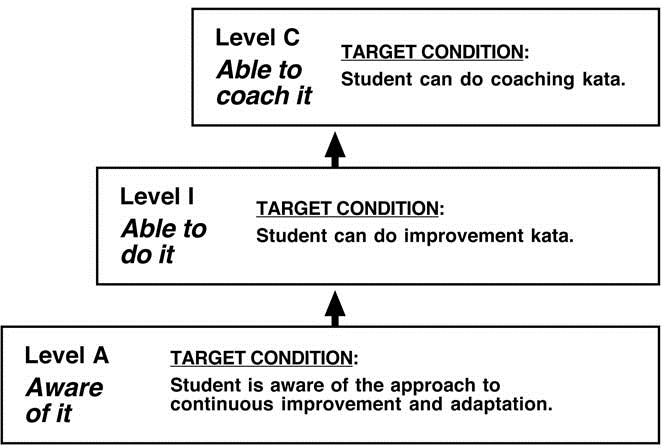

In establishing this target condition, something we do is describe levels of capability that we would like individuals to reach. We have often used the three levels depicted below.

Figure 9-11. Example capability levels

Starting from the bottom of the diagram, Level A (awareness) means that the individual has a basic understanding of what the improvement kata is and how it works. Level I (improvement kata) means that the individual can effectively carry out the improvement kata. Level C (coaching kata) means that the individual can effectively carry out both the improvement kata and a coaching kata.

4. Moving from Current Condition to Target Condition

Once the advance group has defined the target condition, it should involve persons from the next level in the organization, its mentees, in planning how to move from the current condition to the target condition. The advance group should not finalize this part of the plan on its own. It is acceptable for mentors to set a target and sometimes even a target condition, but the mentees should become involved in planning how to achieve that condition. Otherwise it is akin to telling people what to do in traditional fashion.

The overall idea in this part of the plan is for people to learn the improvement kata by repeatedly practicing its routine on real processes under the guidance of a coach. In terms of tactics, this part of the plan should specify the coaching cycles in detail: who will practice when, where, and how? You might lay this out, for example, in monthly increments.

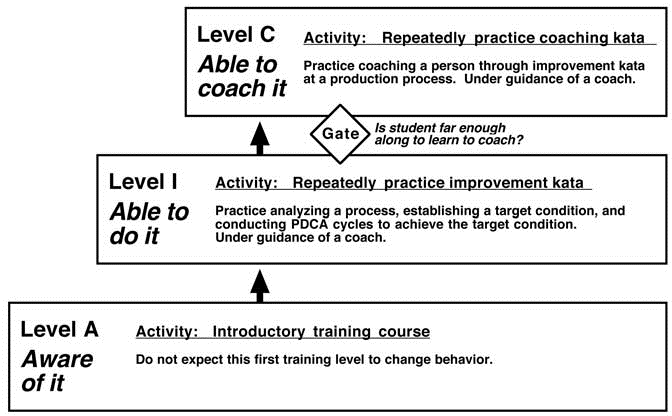

In planning how to move from the current condition to the target condition, we often linked the three levels of capability in Figure 9-11 with levels of training activity as depicted in Figure 9-12.

Starting again at the bottom of the diagram, the training activity at Level A is a classroom course with shop-floor exercises. The purpose of this course is only to create a sense of awareness about what the improvement kata is. The next training level is to practice the improvement kata, which in the diagram is called training Level I. After a person has demonstrated sufficient capability to effectively carry out the improvement kata—this is a gate—they can move to the next level of training, C, where they practice the coaching kata. Moving from Level I to Level C is not a function of time or number of practices completed, but of demonstrated capability.

Figure 9-12. Example training levels

Within the “I” and “C” capability levels individuals will at any point in time, of course, have different skill levels. An interesting view of skill levels is provided by the “Dreyfus model of skill acquisition.”

The three levels of training activity, or whatever levels you may define, can then provide a framework for specifying who will practice

what, when, and how. The table in Figure 9-13 is an example.

As you can see by the horizontal arrows in the table, as people move up in their level of experience, capability, and perspective, some of them teach and coach people in the next level. By coaching the next group, the higher level group can maintain a better sense of the actual situation, that is, people’s true current capabilities. (See benefits of the mentor/mentee approach in Chapter 8.)

This generic table is intended to help you envision how you might move practice-based training through your organization. Real life will not be this neat and orderly, of course. What is depicted in this table will, in most organizations, also involve much more than one year. But with this sort of overall tactic in mind, you can develop your own first plan to match your situation.

increasing involvement over time

Figure 9-13. How training might be moved through an organization

5. Metrics

It is important that we can measure our progress and, in particular, lack of progress. We learn the most from our mistakes! Currently we use two categories of metrics.

- One set of metrics has to do with These might be the start and stop times of coaching cycles, how many processes are coached, who does the coaching, how often the coaching cycles take place, and whether the next step (question five) was taken. However, it is entirely possible to fulfill a specified number of coaching cycles and have little to no improvement effect on the production process. Always bear in mind that the overarching objective is continual improvement of cost and quality perform-

ance at the process level.

- Therefore you should monitor the relationship between coaching cycles (above) and a second set of metrics: to what degree the focus processes are being Such improvement metrics are taken directly from the target conditions at the respective focus production processes.

As mentioned earlier, if the coaching cycles (metric set 1) are being fulfilled as planned but the improvement in the focus processes (metric set 2) are not being reached, then you need to take a closer look at how the coaching is being done.

Also think about and define how these numbers will be obtained. Ideally this is done as simply as possible: with pencil and paper at the process. A good rule of thumb is that, if possible, you should go to the process to get the information you need. Ideally the mentee does not bring metrics to the mentor’s office. It is more like a pull system, if you will, whereby mentor and mentee go to the process to obtain the necessary facts and data there.

Related to metrics, as part of their lean implementation efforts, many organizations have tried utilizing systems of point awards, or similar, to drive and assess progress. Be careful with such systems, since people often end up chasing points rather than a desired target condition. I tend to avoid such schemes.

Problems arise when awards are linked to completion or implementation of activities, which is easy to measure, rather than to attainment of a level of personal competency or of target conditions, which, admittedly, is more difficult to measure. Levels should be awarded based on the student’s demonstrated capability or achievement of target conditions, not on how many courses or practices have been completed or tools implemented.

Include Reflection Times in the Plan

Keep in mind that when you execute a plan and work toward a target condition, you will need to make adjustments based on what you are learning from the unforeseen obstacles and problems you discover along the way. This is one of the reasons we prepare a plan: so we can see what is not going as expected. The advance group should reflect

regularly and make adjustments as necessary. Build this into your plan by scheduling advance-group reflection times, for example, every two weeks.

By conducting reflections—that is, PDCA checks as you work to develop improvement-kata behavior across the organization—you will learn what you need to work on to achieve that behavior. You can conduct reflections in an uncomplicated fashion. Go through the five questions and record on a flip chart what is going as planned (+) and what is not working or not going as expected (—). The inputs for the reflection can come out of the more frequent coaching cycles, which are a kind of process metric.

However, one lesson I have learned is to begin any reflection session with (1) a restatement of the overall theme (for example, “To develop improvement kata behavior in the organization”), and (2) a reiteration of “why we experiment,” in order to calibrate everyone’s thinking before conducting the reflection. In a reflection, people may feel pressure and start defending why they were not able to complete a step as planned. This, of course, inhibits PDCA. It is useful to remind everyone that you are experimenting in order to see obstacles and to learn from them what you need to work on in order to achieve the target condition. You are not looking at individuals and evaluating them, and our success depends upon the reflection being a depersonalized, open, and data-based dialogue.

One more point to reiterate for conducting reflections. We know that the improvement kata is scientific and that it works. If process improvement results are not as expected, then it is not the improvement kata that is faulty but something in our coaching that is still incorrect. Practicing the improvement kata over and over should produce results. If they do not come, then something is wrong in our teaching.

Common Obstacles

In our experimentation there have been many obstacles, many ah-has, and many course corrections. Here are some common obstacles, just as an example. You will find more.

- It is hard for people to resist making a list of action items.

- The five key questions are often difficult for senior leaders to internalize.

- We like doing but not checking and adjusting.

- We jump into solutions and skip over careful observation and analysis.

- People do not understand Toyota-style Both mentor and mentee mistakenly believe that the mentee needs to figure out what solution the mentor has in mind.

- The unclear path to a target condition is uncomfortable for many People like a clear plan in advance even though that is actually only a prediction.

- Iteration (redoing steps) is People feel like they did something wrong when they are asked to look again or repeat a step, yet this is very important for learning and seeing deeply.

- Many people will view this effort as just another project, rather than as developing a new way of At the start, it naturally seems like this effort means adding more work on top of daily management duties, as opposed to it being a different way of conducting daily management.

- At the start, coaching cycles often take too much time and thus become burdensome. Once a target condition has been established, a coaching cycle can often be completed in 15 Less is more. As discussed earlier, rather than making a list of steps, just take one next step and then see where that takes you. Conduct your coaching cycles standing up at the process (target condition information and process data will need to be at the process), and do not let them turn into endless talk sessions. Go through the five questions, find the next step, and that is then the end of the coaching cycle. Take the next step as soon as possible.

Lifelong Practicing

In this chapter we have been talking about developing capabilities and behavior patterns, which, in Toyota’s view, represent the strength of an organization.

The ongoing challenge of kata training is to strive for mastery and perfection, and even the most accomplished Toyota engineers, leaders, managers, and executives will say they are still working toward that goal. The sports metaphor is again appropriate here. Just like athletes, even advanced students and senior leaders will need to keep practicing the katas they learned as beginners, under guidance of a coach.

The never-ending need for improvement and evolution of our processes and products gives us the opportunity to keep honing our skills while working on actual issues and toward real target conditions. While doing so, we should listen to our coaches and others who may detect a bad habit. The elegant trick in this is that while you are practicing, you are also doing something real, always to the best of the current level of your abilities. This is an interesting way to manage continuous improvement and adaptation, and a fascinating way to manage an organization.