To understand Toyota’s improvement kata and coaching kata we need to consider two aspects of the context within which they operate: the business philosophy, or purpose, of the company; and its overall sense of direction.

The Company’s Business Philosophy

The business philosophy of a company does much to define the thoughts and actions of everyone in the organization. However, by “business philosophy” I do not mean those nice, generic statements printed on the poster in the lobby. I mean if you stood in the factory for a day and observed what people do—what is important to them, what gets measured—then what would you conclude is important to this company? As they say at Toyota, “The shop floor is a reflection of management.”

For many manufacturers the company philosophy or purpose would boil down to something like the statement in Figure 3-1.

Many manufacturers:

“Make good products for the customer.”

Figure 3-1. A typical company philosophy

And this is not bad by any means. But consider Toyota’s philosophy in comparison (Figure 3-2).

Toyota:

“Survive long term as a company by improving and evolving how we make good products for the customer.”

Figure 3-2. Toyota philosophy

While this sounds similar to the first philosophy, there is a significant difference. Notice the position of improvement and adaptation in each case. In the first philosophy, improvement and adaptation are an add-on; something we do when there is time or a special need. In the second philosophy, improvement and adaptation move to the center. They are what we do.

Along these lines, here are a few questions to help you think about the position of improvement in your organization. Only you can answer them for yourself:

- Do I view improvement as legitimate work, or as an add-on to my real job?

- Is improvement a periodic, add-on project (a campaign), or the core activity?

- Is it acceptable in our company to work on improvement occasionally?

The last question, in particular, can make things clear. Imagine you were to walk into a manager’s office and say, “We made a nice improvement in process X . . . and next month we will take another look at improving that process further.” That would probably be acceptable. Now imagine that you said, “We produced 400 pieces of product at process X today . . . and next month we will take a look at producing some more product at that process.”

That would not be acceptable at all! And so we can see the relative position that improvement has in our company. If your business philosophy is to improve, then periodic improvement projects or kaizen workshops are okay but not enough. You would only be working on your organization’s core objective occasionally, during periodic events.

At Toyota, improving and managing are one and the same. The improvement kata in Part III is to a considerable degree how Toyota manages its processes and people from day to day. In comparison, non-Toyota companies tend to see managing as a unique and separate activity. Improvement is something extra, added on to managing.

Non-Toyota thinking: normal daily management + improvement

Toyota thinking: normal daily management = process improvement

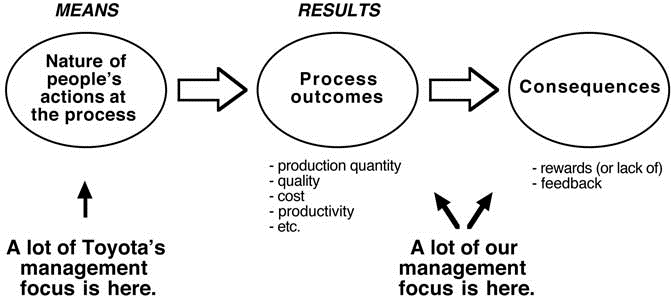

An interesting point is that many of us would probably be afraid to focus so heavily on the second philosophy, improvement, at the expense of the first philosophy, make production. We would feel we were letting go of something we currently try very hard to control, because we’re accustomed to focusing on outcomes, not process details. In our current management approach we concentrate on outcome targets and consequences. In contrast, as depicted in Figure 3-3, Toyota puts considerable emphasis on how people tackle the details of a process, which is what generates the outcomes.

Outcome targets, such as the desired production quantity, are of course necessary. But if you focus on continuously improving the process—systematically, through the improvement kata, rather than just random improvement—then the desired outcomes will come. Making the desired production quantity, for example, will happen automatically when you focus on the details of a process through correct application of the improvement kata.

Figure 3-3. Focusing on means in order to achieve desired results

The following story from before the Second World War, when Toyota made weaving looms, provides an example of this way of thinking. It comes from a Toyota booklet about the spirit and ideas that created the company, and relates how Kiichiro Toyoda (1894–1952), founder of the Toyota Motor Corporation and son of Toyoda Automatic Loom Works founder Sakichi Toyoda, supposedly responded when someone once stole the design plans for a loom from the Toyoda loom works:

Certainly the thieves may be able to follow the design plans and produce a loom. But we are modifying and improving our looms every day. So by the time the thieves have produced a loom from the plans they stole, we will have already advanced well beyond that point. And because they do not have the expertise gained from the failures it took to produce the original, they will waste a great deal more time than us as they move to improve their loom. We need not be concerned about what happened. We need only continue as always, making our improvements.

Does a lean value stream equal lean manufacturing?

Many years ago I visited a small automobile-component factory that ostensibly operated with a lean strategy. And, in fact, the plant sported a fairly short lead time through its value stream. Its strategy involved the following elements:

- Hire recent high school The turnover rate was high, but the labor was young and inexpensive.

- Staff processes with about 40 percent extra operators, which was possible because of the low hourly This was done so that despite problems and stoppages, each process could still produce the required quantity every day with little or no help from indirect staff or management. With extra operators in the line, the operators could dispense with problems themselves (but not eliminate the causes) and still achieve the target output. Autonomous teams, if you will.

- A flat organization, that is, one with few levels of management.

- Inventory levels were kept low, since each process was generally able to produce the required quantity, which is why the lead time through the value stream was Only a little over one day of finished goods, for example, was kept on hand.

The low inventory levels, flat organization, and short value stream, sound “lean,” but here’s the problem: from day to day and week to week the same problems would arise and the operators would simply work around them. This meant that the plant was standing still—not continuously making progress or improving—and that is quite possibly what Toyota fears most of all.

Honesty Required

We are considering business purpose or philosophy early in this book because this is where many companies trying to copy Toyota are, from the start, already on a different path. At this point some honesty is required from you. What is the true business philosophy of your company? While we talk about the importance of providing value for the customer and continuous improvement, more than a few of us are, in truth, focused narrowly on short-term profit margin. The unspoken business philosophy at some companies is simply to produce and sell more. Or it is about exercising rank and privilege, and thus avoiding mistakes, hiding problems, and getting promoted, which become more important than performance, achievement, and continuous improvement.

Direction

Having an improvement philosophy and an improvement kata is important, but not quite enough. Ideally, action would have both form (a routine or kata) and direction. For example, many of us would say that improvement—or “lean”—equals “eliminating waste.” Although this popular statement is basically correct, it is by itself too simple. The negative result of “improvement equals eliminate waste” thinking is twofold: we cannot discern what is important to improve, and we tend to maximize the efficiency of one area at the expense of another, shifting wastes from one to another rather than optimizing and synchronizing the whole.

A classic example of this involves material handling. In the quest to eliminate waste, we often come upon the idea of presenting parts and components to production operators in small containers. The small containers reduce waste at the process because they can be placed close to the operator’s fingertips (less reaching and walking to get parts), and more part varieties can be kept within the operator’s reach (no changeover is necessary for producing different products). Of course, those parts currently arrive from the supplier in large containers on pallets, which are dropped off in the general vicinity of the production operators with a fork truck.

At this point a logistics manager will usually speak up and say, “Wait a minute, let me get this straight. My department is evaluated on its productivity, and you want my people to take parts out of the large containers and repack them into small containers. Then you want my people to get off the fork truck and place those containers near the operator’s fingertips. And since the quantity of delivered parts will now be smaller—because fewer parts can be stored so close to the operator—my people will have to deliver several times a shift, rather than only once or twice per shift. Now we all know that ‘lean’ means eliminating waste. All those extra non-value-added activities would obviously be waste, so this cannot be the right solution.”

I have observed this type of debate many times, and it always goes around and around the same way. Whoever is most persuasive wins and sets the direction for a while, until someone else brings up a different persuasive argument or idea. Or we use a voting technique to make it seem that we’re being systematic and scientific about choosing the direction. What in fact is happening is that the organization is essentially flailing about and frequently shifting direction as it hunts for the “right” solution to implement, and jumps from one potential solution to another. Sometimes an external consultant will be brought in to provide a seemingly clear answer and be the tie breaker, or to be the person to blame in case the choice does not work out.

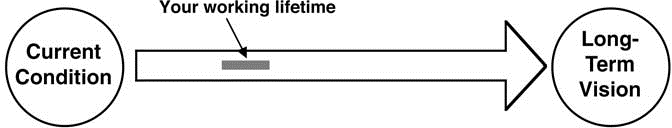

So who is correct in this situation: the production manager who wants small containers, or the logistics manager who wants to avoid extra handling? Under the simple concept of lean equals eliminate waste, everyone is. What is missing here is a sense of direction. Although we may think of adaptation as essentially a reactive activity, it is actually what happens on the way to somewhere. Evolution in nature may not be heading in any particular predefined direction or have any particular boundaries, but for a human organization to be consciously adaptive, it helps to have a long-range vision of where we want to be. That is something we can choose or define, while the adaptation that will take place between here and there is not. By long range I mean a vision that may extend beyond one working lifetime, perhaps even to 50 years or more (Figure 3-4).

Note that a vision, or direction giver, is not simply a quantitative target. It is a broad description of a condition we would like to have achieved in the future. To repeat, the definition of continuous improvement and adaptation I am using in this book is: moving toward a desired state through an unclear territory by being sensitive to and responding to actual conditions on the ground.

Figure 3-4. A vision is a direction-giver

You’ve got to think about big things while you’re doing small things, so that all the small things go in the right direction.

—Alvin Toffler

A long-term vision or direction helps focus our thinking and doing, because without it proposals are evaluated independently, instead of as part of striving toward something.

Defining longer-term direction/vision can be tricky, and even dangerous, however. For example:

- Although we cannot see what is coming, a vision based exclusively on current paradigms, competencies, products, or technologies can limit the future range of our adaptation too Toward that end, a vision should probably focus more on the customer, and broad-scale customer needs, than on ourselves.

- Visions developed in a way that seeks to protect current sacred cows are often so watered down that they are essentially useless for providing

An example of a useful but not overly confining long-term vision is Toyota Motor Corporation’s early vision of “Better cars for more people.” What would this vision, this direction, lead an automobile manufacturer to do? Consider Toyota’s current market position, global presence, and product mix with this old vision statement in mind.

Toyota’s Vision for Its Production Operations

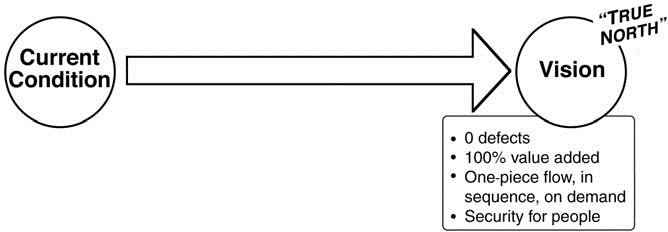

As depicted in Figure 3-5, in its production operations, Toyota has for several decades been pursuing a long-term vision that consists of:

- Zero defects

- 100 percent value added

- One-piece flow, in sequence, on demand

- Security for people

Toyota sees this particular ideal-state condition—if it were achieved through an entire value stream—as the way of manufacturing with the highest quality, at the lowest cost, with the shortest lead time. In recent years Toyota began referring to this as its “true north” for production. You can think of this production vision as “a synchronized one-by-one (1x1) flow from A to Z at the lowest possible cost” or as “one contiguous flow.” Note that Toyota’s production vision also describes a condition, not just a financial or accounting number.

Figure 3-5. Toyota’s vision for production operations

What is a one-piece flow? In its ideal, one-piece flow means that parts move from one value-adding processing step directly to the next value-adding processing step, and then to the customer, without any waiting time or batching between those steps. For many years we called this “continuous flow production.” Toyota now refers to it as “one-by-one production,” perhaps because many manufacturers will point to a moving production line with parts in queue between the value-adding steps and erroneously say, “We have continuous flow, because everything is moving.” Such a misinterpretation is more difficult to make when we use the phrase “one-by-one production.”

Toyota’s production vision, which will be the example of a vision that we use throughout this book, is actually an old concept and it does not come from Toyota or Japan. The advantages of sequential and 1x1 flows have been known for a long time, and in one form or another the flow ideal has been pursued on and off again for centuries. Some examples:

- During the mid-1500s the Venetian arsenal developed a system for mass production of warships, and could produce nearly one ship a day with standardized parts on a sequential, production- line basis.

- In the late 1700s Oliver Evans developed a sequence of machines and conveyance devices that connected all parts of the flour milling process into one continuous system. Grain was poured in at one end of the mill and flour came out the other, without sacks of material (batches) being moved around between the processing steps inside the mill.

- In the 1820s at the Springfield Armory in Massachusetts, Thomas Blanchard developed a sequence of 13 or 14 machines to process gun stocks.

My colleague Gerd Aulinger takes a perhaps even more insightful and universal view on the quest to move closer to 1x1 flow, with examples such as the following:

- In the nineteenth century if you wanted to hear Strauss play a waltz, you had to invite him to your Later we could go to the store to buy records and CDs. Today, music plays on your mp3 player, downloaded from the Internet. Payment for that music file is made without paper money through an automatic charge to your credit card.

- Prior to the fifteenth century if you wanted a book, someone had to write it out by hand. Then Gutenberg began printing them. Eventually publishing companies were born and you could buy a book at the store, during business Now you order the book online anytime, and perhaps it is even downloaded to your reading device or printer.

- At one time we sent letters by horse Then came mail coaches. Following that came once-daily delivery to your doorstep. Today we communicate at any time, via telephone, e-mail, and Skype.

Remarkably, we still find plenty of organizations that argue internally about whether to accept this endless trend toward 1x1 flow—as if it were something we have the power to control.

When I first came across Toyota’s true north vision, I thought I had caught a mistake, and indicated as much to a Toyota person. “One hundred percent value added is probably not even achievable,” I said. “If you just move the product from one spot to the next then there is waste!” The response was, “Well, it could be that our production true north is theoretical and not achievable, but that does not matter. For us it serves as a direction giver, and we do not spend any time discussing whether or not it is achievable. We do spend a lot of effort trying to move closer to it.”

In other words, it is acceptable and perhaps even desirable for the vision to be a seeming dilemma and thus a challenge.

The Toyota person’s comments reminded me of the story about two people being chased by a hungry tiger. When one of them stops to put on some running shoes, the other says, “What are you doing? Do you not see the tiger coming?” The first person replies, “Yes I do, but as long as I am ahead of you I’ll be fine.” In a way, this is part of Toyota’s strategy. Toyota is by no means perfect and is still a long way from its ideal state condition. But as long as the product is what the customer wants, whoever is ahead on the way there will essentially get the money and survive. A trick for manufacturers is to stay ahead of your competitors in this direction.

The striving for improvement in this direction, in all work activity, is a guiding light in Toyota’s manufacturing operations, and apparently does not change. Both the company’s philosophy of survival through improvement plus this direction giver have remained consistent beyond the tenure of any one leader.

As production expanded during the 1950s, Toyota shifted its priorities from improving capacity and basic manufacturing technology to developing an integrated, mass-production system that was as continuous as possible from forging and casting through final assembly.

—Michael A. Cusumano, The Japanese Automobile Industry

Toyota’s progress toward this true north condition is by no means linear, but due in part to this consistent focus for over 50 years, Toyota has achieved a lead in eliminating waste and improving the flow of value. And it continues to move forward.

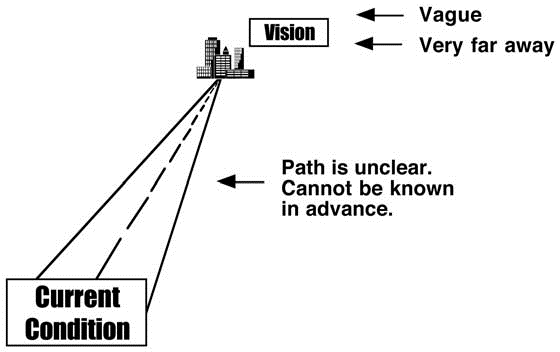

Vision as an Overall Direction Giver, but Not Much More

Toyota’s production system, for example, seeks to reduce cost and improve quality by moving ever closer to a total, synchronized, wastefree, one-by-one flow. But how do we get an organization of hundreds or thousands or tens of thousands of people to work continuously and effectively in the direction of a vision? We cannot simply move from where we are today to a low-cost, synchronized one-by-one flow from start to finish. In fact, it is dangerous to jump too far too fast; to cut too much inventory and closely couple processes too soon. A vision is far away, and the path to it is long, unclear, and unpredictable (Figure 3-6). How do we find and stay on that path?

Figure 3-6. A vision serves primarily as a direction giver

Figure 3-7. Target conditions are where the action is

Target Conditions

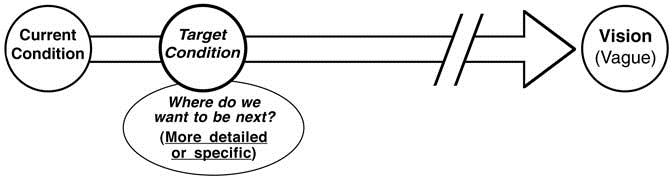

Toyota moves toward a vision by working with something I call “target conditions.” Across the organization Toyota people learn to set and work toward successive target conditions in the direction of whatever vision is being pursued (Figure 3-7). This condition typically represents a step closer to the vision and a challenge that goes somewhat beyond current capability. You can think of a target condition like a much shorter-term desired state that is more clearly defined than the distant vision. Like the vision, an interim target condition is also not a financial or accounting target, but a description of a condition.

Once a target condition is defined, it is not optional nor easily changeable. It stands. How to achieve that target condition is optional and can tap into what humans are good at: roll-up-your-sleeves effort, resourcefulness, and creativity to achieve new levels of performance. That is, if they have a kata and are well-managed. Target conditions are a component of Toyota’s improvement kata, and we will look at them closely in Chapter 5.

Utilizing the Sense of Direction to Manage People

How does Toyota utilize its production vision to help manage people? A couple of examples will clarify this.

Example 1: Sensor Cables

In visiting the assembly area of a factory that produces automotive ABS-sensor cables (wires with a connector at one end and a sensor at the other), we found that the batch size in the assembly processes was one week. That is, a five-day sales quantity of one sensor-cable type is produced, and then the assembly process is changed over to produce a five-day batch of a different type. A quick calculation showed, however, that there was enough free capacity to permit more changeovers and smaller assembly batch sizes. The assembly area could set a target condition of a one-day batch size, rather than the current five days, and achieve that without even having to reduce the already short changeover time.

In the conference room, we pointed out the potential for smaller batch sizes to the management team. The benefits of smaller lot sizes are well known and significant: closer to 1x1 flow, less inventory and waste, faster response to different customer requirements, less hidden defects and rework, kanban systems become workable, and so on.

Almost immediately the assembly manager responded and said, “We can’t do that,” and went on to explain why. “Our cable product is a component of an automobile safety system and because of that each time we change over to assembling a different cable we have to fill out lot-traceability paperwork. We also have to take to the quality department the first new piece produced and delay production until the quality department gives us an approval. If we were to reduce the assembly lot size from five days to one day we would increase that paperwork and those production delays by a factor of five. Those extra non-value-added activities would be waste and would increase our cost. We know that lean means eliminate waste, so reducing the lot size is not a good idea.”

The plant manager concurred, and therein lies a significant difference from Toyota. A Toyota plant manager would likely say something like this to the assembly manager: “You are correct that the extra paperwork and first-piece inspection requirements are obstacles to achieving a smaller lot size. Thank you for pointing that out. However, the fact that we want to reduce lot sizes is not optional nor open for

discussion, because it moves us closer to our vision of a one-by-one flow. Rather than losing time discussing whether or not we should reduce the lot size, please turn your attention to those two obstacles standing in the way of our progress. Please go observe the current paperwork and inspection processes and report back what you learn. After that I will ask you to make a proposal for how we can move to a one day lot size without increasing our cost.”

Using Cost/Benefit Analysis in a Different Way

As the sensor cable example illustrates, without a direction we tend to evaluate proposals individually on their own merits, rather than as part of striving toward something. This creates that back-and-forth, hunting-for-a-solution, whoever-is-currently-most-persuasive effect in the organization.

Specifically, without a sense of direction we tend to use a shortterm cost/benefit analysis to decide and choose on a case-by-case basis whether or not something should be done—in which direction to head and what to do—rather than working through challenging obstacles on the way to a new level of performance. How many times have you witnessed a potentially interesting though still unformed idea quickly torpedoed and killed with the question, “Is there a financial benefit to that?”

Toyota uses cost/benefit (CBA) analysis too, but differently than do we. While we have learned to utilize CBA to determine what to do, at Toyota one first determines where one wants or needs to be next—the target condition—and then cost/benefit analysis is utilized to help determine how to get there. At Toyota, CBA is used less for deciding whether something should be done, and more for deciding how to do it.

Traditional: CBA determines direction; that is, whether we do something or not. “This proposal is too costly? Then we must do something else.”

Toyota: CBA helps define what we need to do to achieve a predefined target condition. “This proposal is too costly? Then we must develop a way to do it more cheaply.”

Do not think, however, that Toyota’s approach is about achieving target conditions at any cost. Toyota has strict budgets and target costs. The idea is to first determine where you want to go, and then how to get there within financial and other constraints. This is where the sense of direction from the vision plays its role. Do not let financial calculations alone determine your direction, because then the organization becomes inward-looking rather than adaptive, it oscillates on a case-by-case basis rather than striving toward something, and it seeks to find and implement ready solutions rather than developing new smart solutions. An economic break-even point is a dependent variable, not an independent constraint that determines direction.

Example 2: New Production Process

When a new assembly process is being designed, there are usually a few different process options from which to choose. For example, there may be a fully automated line concept, a partially automated version, as well as a manual line concept. When we run these options through a cost/benefit analysis—a return-on-investment, or ROI, calculation—more often than not the fully automated option wins and is what we select. Later, when the line is in place, there are complaints that the automated line does not fit well with the situation.

To follow Toyota-style thinking, we would take a different approach. First we would determine where we want to be. In this case that means determining what type of assembly process is most appropriate for the particular situation. Fully automated, partially automated, and manual lines all have their place, depending on the situation, and all of them can be a “lean line.” In the early start-up phase of production for a new product, the product’s configuration is still apt to change and the sales volume ramp-up may be different than expected. In this situation it can make sense to begin with a flexible, easily altered manual line and move to higher levels of automation when the product matures and sales volume increases.

Now comes the cost/benefit analysis, which, let’s say, shows that the manual line design is too expensive. In the Toyota way of thinking, this does not mean that the manual line option is dropped. The target condition, a manual line, has already been defined and stands. What the negative outcome of the cost/benefit analysis tells a Toyota manager is that more work is needed on the design of the manual line, in order to bring it into the target cost objective. The manager will ask his engineers to sharpen their pencils and go over the design again, and this will continue iteratively until the target condition is reached within budget constraints. The sense of direction was used to manage people—in this case the engineers who were charged with developing a new production process.

Stay Home

One lesson implicit in this chapter is that we should not spend too much time benchmarking what others—including Toyota—are doing. You yourself are the benchmark:

- Where are you now?

- Where do you want to be next?

- What obstacles are preventing you from getting there?

For example, if you find that your technical support staff cannot respond quickly enough to machine problems, you might think, “I wonder how Toyota handles this?” Or you could stay home and ask, “How fast do we want our technical support to respond? What is preventing that from happening? What do we need to do to achieve the desired condition?”

Remember, the ability of your company to be competitive and survive lies not so much in solutions themselves, but in the capability of the people in your organization to understand a situation and develop solutions.

And you don’t have to be perfect, just ahead of your competitors in aspects of your product or service.